The diverse face of biology

Charles Darwin. Carolus Linnaeus. Gregor Mendel. Their names and contributions to science appear in every biology textbook, and rightly so, but is it really true that the history of biology is dominated by white men? Men and women of all backgrounds have contributed heavily to the current knowledge and continue to do so. It is time to recognise the diverse face of biology.

The good news is that the scientists portrayed in textbooks are getting more diverse. In recent years, the ratio of women highlighted has increased proportionally with the number of women in the field, suggesting that textbooks are beginning to match a changing academic landscape. The bad news is that if diversification of textbooks continues at its current rate, it will take another 500 years for mentions of Black scientists to accurately reflect the number of Black students studying biosciences at university.1 That needs to change. As part of our commitment to promoting diversity, we want to make a step towards more inclusive representation of biologists. And that is why we have chosen to highlight some of the influential Black scientists who have greatly advanced their field.

John Edmonstone was born into slavery in the late 1700s on a plantation in Guyana owned by the Scottish politician, Charles Edmonstone. When Charles’ future son-in-law, and pioneering naturalist, Charles Waterton was invited to visit the plantation, John was assigned as his assistant on expeditions into the surrounding rainforests to collect bird specimens. The hot and humid conditions meant the birds had to be preserved quickly to avoid rotting, so Waterton taught John taxidermic preservation. During these expeditions, John also gained immense knowledge of South America’s diverse flora and fauna. They embarked on several trips together, which are documented in Waterton’s novel ‘Wanderings in South America’.

In 1807, The Slave Trade Act made the purchase or ownership of slaves illegal within the British Empire. So when John travelled to Glasgow with Charles Edmonstone, he gained his freedom and moved to Edinburgh to begin his new independent life. He took up residence at 37 Lothian Street, working as a taxidermist for the Natural Museum and teaching taxidermy skills to students at the University of Edinburgh.

One of his students was a 17-year-old Charles Darwin. For one guinea a week (around £103.79 today), Darwin hired John for 40 weeks of daily lessons in taxidermy. John taught Darwin the taxidermy techniques he would later use to preserve his Galapagos finches, which in turn led him to develop his theory of evolution by natural selection. In his memoir, Darwin also recalls enjoying their hours of inspiring conversations together and describes John as a man of high intellect. After Darwin shared his interest in Waterton’s novel ‘Wanderings in South America’, John recounted his experience on the expeditions in his homeland. One can imagine how this sparked Darwin’s imagination, and it’s unlikely to be coincidence that soon after Darwin graduated, he set off on his voyages aboard the HMS Beagle to chart the South American coastline and see the region and wildlife that John had spoken about.

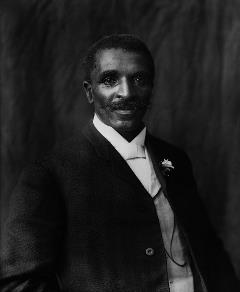

The start of George’s life was traumatic. He was born into slavery on Moses Carver’s farm in Missouri, but kidnapped at just a few weeks old, along with his mother and sister, by confederate raiders who sold them in Kentucky. Moses was only able to find George, but brought him back to Missouri where he and his wife, Susan, raised George as their own. Susan taught George to read and encouraged him to help in her kitchen garden and make herbal medicines. George became fascinated by plants and was soon experimenting with natural pesticides, fungicides, and soil conditioners. Local farmers began to call George ‘the plant doctor’, because he was able to tell them how to improve the health of their garden plants. Susan and Moses saw George’s potential and found a school for him to attend.

George faced much discrimination when trying to access higher education. Despite an impressive application essay initially securing him a full scholarship to Highland Presbyterian College in Kansas, he was turned away once they realised he was Black. He managed to save money while working on various farms and ranches before he was finally able to enrol at Simpson College, Iowa, to study art and piano. His precise detail in paintings of plants captured the attention of his instructor, Etta Budd, and she encouraged him to apply to Iowa State Agricultural School to study botany.

George later became the first African American student to earn his Bachelor of Science in 1894, and his work on fungal infections common to soybean plants prompted his professors to request he remain as part of the faculty to work on his master’s degree (awarded in 1896). He swiftly became director of the Iowa State Experimental Station, conducting experiments in soil management and crop rotation aimed at helping Southern US agriculture. Carver encouraged Southern farmers to plant peanuts, sweet potatoes, and soybeans to restore nitrogen in areas where single-crop cultivation of cotton had depleted the land. When production of these crops exceeded demand, George developed more than 300 commercial products from peanuts, and 118 from sweet potatoes . Years of research helped to establish the South as a major new supplier of agricultural products and saved countless farmers from ruin.

George continued his exceptional work for the remainder of his life. In 1940 he donated his life savings to establish the Carver Research Foundation at Tuskegee, Alabama, for continued research in agriculture. He later used his celebrity to promote science, writing a newspaper column and touring the USA to speak on the importance of agricultural innovation.

George’s work was recognised and celebrated in his time. He acted as advisor to notable people of the era including President Roosevelt, Mahatma Gandhi, and Henry Ford. He was also the recipient of the Spingarn Medal and a member of the British Royal Society.

Wangari Maathai

Wangari Maathai was born on 1 April 1940 in Nyeri, Kenya. She grew up in a small village where her father worked as a tenant farmer. Wangari recounted that a childhood in which she spent much of her time in the field observing nature taught her “respect for the soil and its bounty”.

Although it was uncommon at the time for girls to be educated, Wangari’s older brother recognised her sharp intellect and persuaded their parents to send her to school, and so she was enrolled at a local primary school when she was 8 years old. An excellent student, Wangari was able to continue her education at the Loreto Girls’ High School, where she continued to excel. In 1960, she won a scholarship to attend university in the USA. Wangari attended Mount St. Scholastica College in Kansas, earning first a bachelor’s degree in biology in 1964 and subsequently completing a master’s degree in biological sciences at the University of Pittsburgh.

Although she enjoyed her time in the USA, Wangari returned to Kenya to study veterinary anatomy at the University of Nairobi. In 1971, she became the first woman in Eastern or Central Africa to earn a PhD. Following the completion of her PhD, she continued to make history and pave the way for women in science by joining the faculty of the University of Nairobi as a professor of veterinary anatomy, becoming both the first woman to hold a professorship at the school and, later, the first woman to chair a university department in the region.

Wangari was also active in the National Council of Women of Kenya and became Chair in the 1980s. During her time serving in the National Council of Women, Wangari introduced the idea of community-based tree planting, and continued to develop this idea into a grassroots organisation, the Green Belt Movement, whose main focus is to increase environmental conservation and reduce poverty through tree planting. Wangari is internationally admired for her dedication to environmental conservation, human rights, and democracy, and has received numerous awards, most notably the Nobel Peace Prize in 2004. She continued to promote equality and environmental conservation in the political arena, and in 2002 Wangari was elected to the Kenyan Parliament with 98% of the votes, before being appointed, by President Mwai Kibaki, as the Assistant Minister for Environment, Natural Resources and Wildlife.

Professor Wangari Maathai passed away in 2011. As a women in science and politics, she pushed the envelope on gender equality and made significant progress in closing the gender gap. She overcame all obstacles thrown at her and left her mark on our planet—thanks to her efforts, more than thirty million trees have been planted. Her amazing life story can be read in her own words in her 2006 memoir Unbowed.

It is important to celebrate the incredible achievements of these inspiring people, and to make sure the many contributions other Black scientists have made to the field of biology are recognised. However, it is also important to remember that the lack of diversity in science is a result of much more than just underreporting. The SEB is committed to actively creating a welcoming, supportive environment to all, and we will continue to provide resources and challenge perpetuated systemic inequalities. We need to recognise the contributions of underrepresented groups to the scientific community, and we need to make it easier for others to follow in their footsteps.

The Unsung Scientists Timeline

The SEB wants to increase recognition of the achievements and contributions of the Black community to the field of biology through the creation of a timeline of influential Black scientists throughout history and into the present day.

We are asking our members and supporters to get involved with this venture and submit their own additions to the timeline. If you would like to get involved, please create a short biography of a biologist who has inspired you in the format outlined below. All submissions to be sent to: [email protected]

Contributors to the timeline will be automatically entered into a prize draw for the chance to win three books celebrating the lives of just a handful of the inspirational scientists to be featured.

Take a look at the timeline and find out more on how to submit your entry on our website: https://www.sebiology.org/SEBplus/equality-and-diversity/black-history-month/the-unsung-scientist-timeline